The silent galleries of museums and the hushed halls of private collections hold more than just aesthetic beauty; they are repositories of human history, vulnerable to the relentless march of time. For centuries, the preservation of these treasures was an art form in itself, relying on the intuition and experience of conservators. Today, a quiet revolution is underway, one that merges the meticulous eye of the art historian with the precise tools of the scientist. The field of art conservation science has emerged as a critical discipline, employing advanced technologies not merely to restore, but to proactively extend the lifespan of our cultural heritage for generations to come.

The fundamental enemy of any artwork is change. Whether painted on canvas, carved from stone, or printed on paper, all materials are in a constant, albeit slow, state of degradation. Light, particularly the ultraviolet and infrared spectrums, acts as a powerful agent of destruction, causing pigments to fade and organic materials like paper and textiles to become brittle. Fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity cause materials to expand and contract, leading to cracks, flaking paint, and warping. Pollutants in the air, both gaseous and particulate, can settle on surfaces, catalyzing chemical reactions that etch, discolour, or corrode. The mission of conservation science is to understand these complex decay mechanisms at a molecular level and to develop strategies to halt or dramatically slow them.

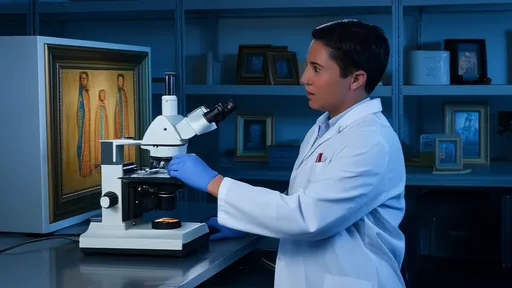

This scientific journey often begins with the power of sight, but not as the human eye perceives it. Multispectral and hyperspectral imaging have become indispensable tools in the conservator's arsenal. By capturing light reflected from an artwork at wavelengths far beyond the visible spectrum, these technologies reveal secrets hidden for centuries. Underdrawings—the initial sketches made by an artist—become visible, offering profound insights into the creative process and artistic intent. Earlier restoration attempts, now discoloured or degraded, can be mapped to guide current treatments. Perhaps most importantly, these imaging techniques can identify areas of nascent degradation, such as the formation of harmful salts or the early stages of pigment alteration, long before they become visible to the naked eye. This allows for preemptive conservation, addressing problems at their source rather than merely treating their symptoms.

Beyond seeing, scientists must understand the very composition of an artwork. Here, non-invasive analytical techniques are paramount. X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, for instance, allows a conservator to point a handheld device at a painting and, within seconds, receive a detailed elemental breakdown of the pigments used. This is crucial for authentication, dating, and understanding an artist's palette. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy helps identify organic materials—specific types of binding media like egg tempera or linseed oil, or varnishes that have yellowed with age. By understanding the exact chemical makeup, conservators can select the most compatible and effective cleaning agents and consolidants, ensuring treatments do not cause unintended long-term damage.

The battle against environmental degradation is fought on a macro scale within the very buildings that house art. The era of static, one-size-fits-all climate control is giving way to a new paradigm of smart environmental monitoring. Galleries and storage facilities are now equipped with vast networks of wireless sensors that continuously track temperature, humidity, light levels, and pollutant concentrations. This real-time data is fed into sophisticated building management systems that can make micro-adjustments to maintain an environment perfectly tailored to the specific needs of the objects within. A room containing ancient wooden sculptures, which require a stable and slightly higher humidity, can be maintained adjacent to a gallery of metallic objects that need drier conditions. This data-driven approach is not only more effective but also more energy-efficient, representing a sustainable model for large-scale preservation.

Perhaps the most futuristic frontier in art conservation lies at the nanoscale. Nanotechnology offers revolutionary solutions to age-old problems. Conservators are now experimenting with nano-materials for cleaning. For example, highly porous hydroxyapatite nanoparticles can be applied as a gel to the surface of a painting. These nanoparticles are engineered to have a stronger affinity for the harmful salts and grime on the surface than for the original paint layers beneath, lifting away pollutants with unprecedented precision and safety. Similarly, nano-sized calcium hydroxide particles can be suspended in alcohol and applied to deacidify and strengthen brittle paper and canvas, effectively reversing chemical decay from within the material's structure.

For three-dimensional objects, particularly large-scale outdoor sculptures and architectural elements, the challenges of weathering are immense. Here, science has developed innovative protective systems. Electrochemically assisted desalination techniques can be used to draw damaging salts out of porous stone like marble, preventing surface spalling and powdering. Advanced polymer coatings, some with self-cleaning properties inspired by the lotus leaf, are being formulated to create invisible, breathable barriers that shield metal surfaces from corrosive pollutants and moisture while allowing the material to "breathe," preventing trapped vapor from causing damage from within.

The integration of these technologies is creating a new digital ecosystem for conservation. High-resolution digital imaging, 3D laser scanning, and the data from analytical instruments are being compiled into sophisticated digital twins of artworks. These are not simple photographs but complex, data-rich virtual models. Conservators can use these twins to monitor minute changes over time, simulate the effects of different environmental scenarios or treatment options, and create a permanent record of the object's condition. This becomes an invaluable resource for future generations of conservators, providing a baseline of data that stretches back decades.

Despite these remarkable advances, the field is guided by a fundamental ethical principle: reversibility. Any intervention, no matter how scientifically advanced, must be as reversible as possible. The goal is never to impose a permanent change but to extend the object's life with the lightest possible touch, ensuring that future conservators with even better technology and understanding are not locked in by the decisions made today. This humility in the face of irreplaceable cultural objects is what separates conservation from restoration.

The work of art conservation scientists is a profound dialogue between the past and the future. It is a discipline built on the conviction that a Rembrandt portrait, a Ming dynasty vase, or a medieval tapestry is not a static relic to be kept under glass until it fades away. They are living documents of human achievement, and it is our responsibility to employ every tool at our disposal—from the nano-probe to the climate sensor—to ensure their stories continue to be told. Through this marriage of art and science, we become not just curators of beauty, but active guardians of memory, granting the masterpieces of yesterday a renewed lease on life for the audiences of tomorrow.

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025

By /Aug 28, 2025